The ancient pottery that was made in Japan around 14,500 BCE is called “Jomon.” These ceramic pottery were clay-fired decorative figurines, vessels and pots. The Jomon culture in Japan started during the Paleolithic era, and continued until the Neolithic era. Today, the total intervening years from 14,500 BCE to 2,000 BCE is considered as the Japanese Stone Age Art period.

The Jomon vessels were influenced by pottery from China, which spread across the Siberian border before crossing the Sea of Japan to reach Honshu. Early samples of Jomon ceramic art were jars and simple bowls, decorated with rope markings. The designs were refined during the Neolithic era, where more varieties in shape and decorations were introduced. Likewise the firing methods became refined, and there were evidences that primitive kilns were used. This was also the time when the strange, round-eyed clay figurines with rotund bodies, called dogū, were created.

Buddhist temple art

Japanese medieval Buddhist art are more preserved in Japan compared to neighboring Korea and China. The first wave of this art form reached Japan from the Baekje Kingdom of Korea when the king of Korea sent a gilt-bronze figure of Buddha to the Japanese Emperor. Wood became a favorite medium for sculpture around the 7th and 8th centuries. Wood was smoothly curved and polished, with the sculptors creating forms with gentle contours decorated with linear patterns. However, the best example of this period was the free-standing and huge bronze Buddhist trinity at the Yakushi temple in Nara. The only surviving example is the one at the Todai temple, which was made from metal possibly weighing about five tons.

Zen paintings in ink

The practice of Buddhism was still apparent when the Zen paintings were later developed. The monks, with their skills in concentrated meditation and austerity, sought enlightenment by dedicating their day in creating delicate paintings. Later, the techniques were adopted by the warrior class of the Kamakura Shogunate. The samurais practiced the Buddhist techniques to prepare themselves for war. In their martial art techniques, each of their stroke using a spear, bow or sword needed to be decisive, immediate and spontaneous and with minimal movements, which was also applied to how they painted.

During the Edo period, the more strict style of Zen painting was reintroduced, which focused more on directness and simplicity. Niten, a noted Samurai and ink painter was the foremost painter during this period. His works were characterized by swift and decisive brushstrokes. Contemporaries of his caliber included Sotatsu and Koetsu. Both of them were decorative artists as well as ink-painters (not in the Zen style) and they were credited for reviving the art of Yamato-e.

The strictness of the Zen discipline was loosened during this period and the tea ceremony, which was formerly a religious practice of the Buddhist monks became an aesthetic activity.

Yamato-e, the secular painting style

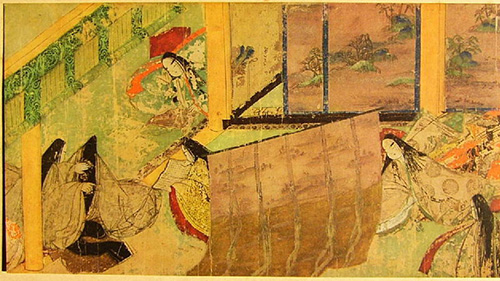

Essentially, the Japanese painting called Yamato-e started from the painting styles of the Tang dynasty of China. It was a court style of painting that flourished during the Kamakura and Muromachi periods and showed something more colorful, decorative and formal as opposed to the Zen ink paintings.

In its early years, most of the Yamato-e paintings were portraits of dignitaries of the court done by Fujiwara Takanobu, which showed stylized faces, decorative detailing and emphasized graphic designs that bordered on simplicity.

Painted scrolls also became an important fixture of Yamato-e, particularly the emakimono, which was a form of long narrative scroll, basically functioning as an illustrated novel. One of the greatest examples of this is the “The Tale of Genji” that showed the courtly life of Lady Murasaki during the 11th century. In this scroll, the status and identity of the figures were defined by their robes. However the faces of the figures were unidentifiable. All of them were oval shapes, with tiny dots for eyes and hooks for noses. Interior scenes were illustrated since the buildings did not have roofs.

Among the most dramatic in this genre were the Ban Dainagon scrolls that were produced in the 12th century in Kyoto, which depicted people from all walks of life, showed in various actions that expressed emotions that were oftentimes violent. The Tosa family school dominated the art scene. Their artists developed the techniques of adding golf-leaf, richer colors and other surface decorations.

The penultimate period for Yamato-e was reached when the Shogunate was transferred from Kyoto to Edo in the early part of the 17th century. The style of Yamato-e was revived and introduced to genre paintings particularly the screens painted by Matsuura, where the figures showed beautiful dresses worn by ladies. This style became the subject matter for the developing art of Ukiyo-e, started by Moronobu for his book illustrations. Other artistic developments during the Edo period were Origami and lacquer painting. The Japanese artists became highly skilled in painting miniscule lacquer dishes and cups, especially the “inro” or the small medicine boxes with compartments.

Photo Attribution:

Featured and 1st image by Chris 73 / Wikimedia Commons

2nd image by Imperial court in Kyoto [Public domain], <a href=”https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AGenji_emaki_azumaya.jpg”>via Wikimedia Commons</a>