Modern art has evolved rapidly due to the changes in our society. The Dadaists, as they rebelled against traditional values and society, have opened up new paths for art to take. As the new avant-garde, they have innovated and created art that is as expressive as their classic predecessors, though it is still disappointingly not beautiful to look at. But that’s to be expected: art is an expression, and those trying to express the modern era while they feel the disgust for it would naturally make ugly yet expressive art.

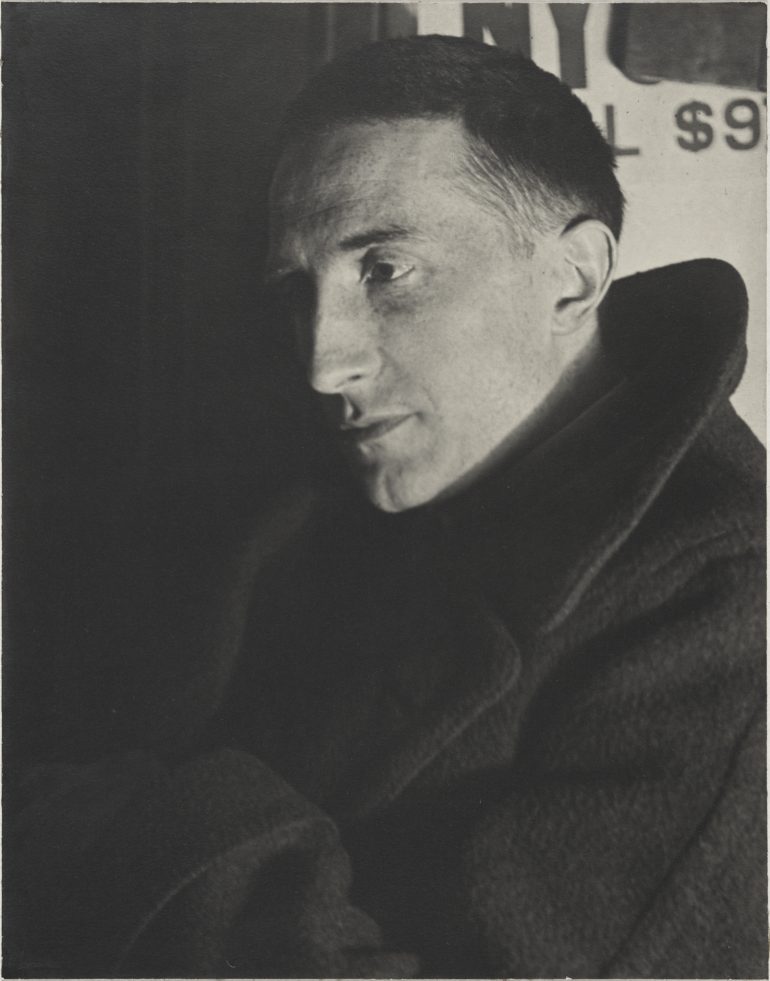

One such artist is Marcel Duchamp. Looking at his works, one can already feel that among the artist of his time he is the best of them all. He is “the most avant-garde of the avant-garde,” if there’s a need to accurately describe him. Only he “has the balls” to put a moustache and goatee on the Mona Lisa, like how kids would do on their textbooks’ illustrations, and call it art (or anti-art, since Dadaism is, after all, anti-art).

Early Life

Duchamp was born in France in 1887, in Blainville-Crevon, around the Normandy Region. He has two elder brothers, Jacques Villon and Raymond Duchamp-Villon, who were also artists. The family he was born is a well-to-do middle class and is well educated, so it isn’t weird for Duchamp to set his eyes to become an artist like his two brothers. He began to train in 1902 and two years later he went to the Academie Julian in Paris to study art. He did admit later on that, rather than an artist, he was actually more interested in playing billiards at the time.

His initial works, after he left the Academy in 1905, was in neo-Impressionism and Nabis. He also did lots of drawings in Toulouse-Lautrec style. In the beginning, he didn’t have any notable work. But he eventually moved on to study cubism from the likes of Roger de La Fresnaye and Frank Kupka. In 1911 he started making his own interpretation of cubism and, the following year, became part of Section d’Or, a cubist group. From Kupka, he also learned a bit of Futurism and chronophotography. Portrait of Chess Players in 1911 and Passage From the Virgin to the Bride in 1912 are just some of his works during that time.

It was just after learning Cubism that he eventually grew tired of art that pleases the eyes (which he calls ‘retinal’ art). True to his avant-garde nature he instead wanted to make art that ‘pleases the mind’ instead.

Pleasing the Mind

Easy to say, hard to do. And Duchamp eventually had to turn his back on everything he had learned at that point and examined his art. There, he tried to create art that ‘pleases the mind’ and came up with The Bicycle Wheel Perched on a Stool, one of the Three Standard Stoppages which is a result of his research. The L.H.O.O.Q. in 1919, which is essentially a moustache and goatee on the Mona Lisa, is his take on the iconoclastic and anti-art Dadaism that, while it certainly isn’t pleasing to look at, the pleasure the minds get is similar to that of a child as he scribbles moustaches and goatees on books. The Dadaists socialists, however, took it to mean as an attack on the bourgeois. Later it was revealed that the face was a bit more to the likeness of Duchamp. Instead of an attack, it looked more like a joke where he clowns around with his own face on the world’s most famous pose. And you can see how having fun ‘pleases the mind’ more than attacking the imaginary bourgeois menace. These new works are part of the more than 20 ready-made art that he created over the years, many of which were lost in time.

That’s not the best of Duchamp, however. It was in 1913 that he started planning his most famous work yet: The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors. In the same year Duchamp created the work that gave him the reputation as the best: the Nude Descending a Staircase, No 2. The work everyone remembers as the one that got him attacked for in the Armory Show in New York.

Last Days

After the creation of The Fountain, which is widely considered as one of the precursors of Junk art, and of L.H.O.O.Q. in 1919, he settled down in New York to found the New York branch of Dadaism, along with Picabia and Man Ray. Dadaists and Surrealists around the world celebrate his works and consider him as part of them. In truth, he never really claimed any allegiance to any specific movement, but Cubists, Dadaists, and Surrealists all seem to want to claim his fame.

Duchamp died in 1968 but his ideas of true philosophical freedom still live on. The Fountain remains as “the most influential artwork of the 20th century.”

First Image: Portrait of Marcel Duchamp by Man Ray, via Wikipedia

2nd Image: L.H.O.O.Q. by Marcel Duchamp, via Christies