Tattooing is a body-modification art form that has been around for centuries. The earliest mention of it was in the writings of James Cook, who saw it during his first voyage to the Pacific late in the 19th century. At that time, the word he used was its Polynesian name, tatau. It became a loan word in English, first written as tattow before it evolved into the present spelling – tattoo. In Japan, it is called irezumi while in New Zealand, it is called tā moko. It has always been a part of Māori culture. It’s about belonging and about beauty that is beyond its skin deep impression.

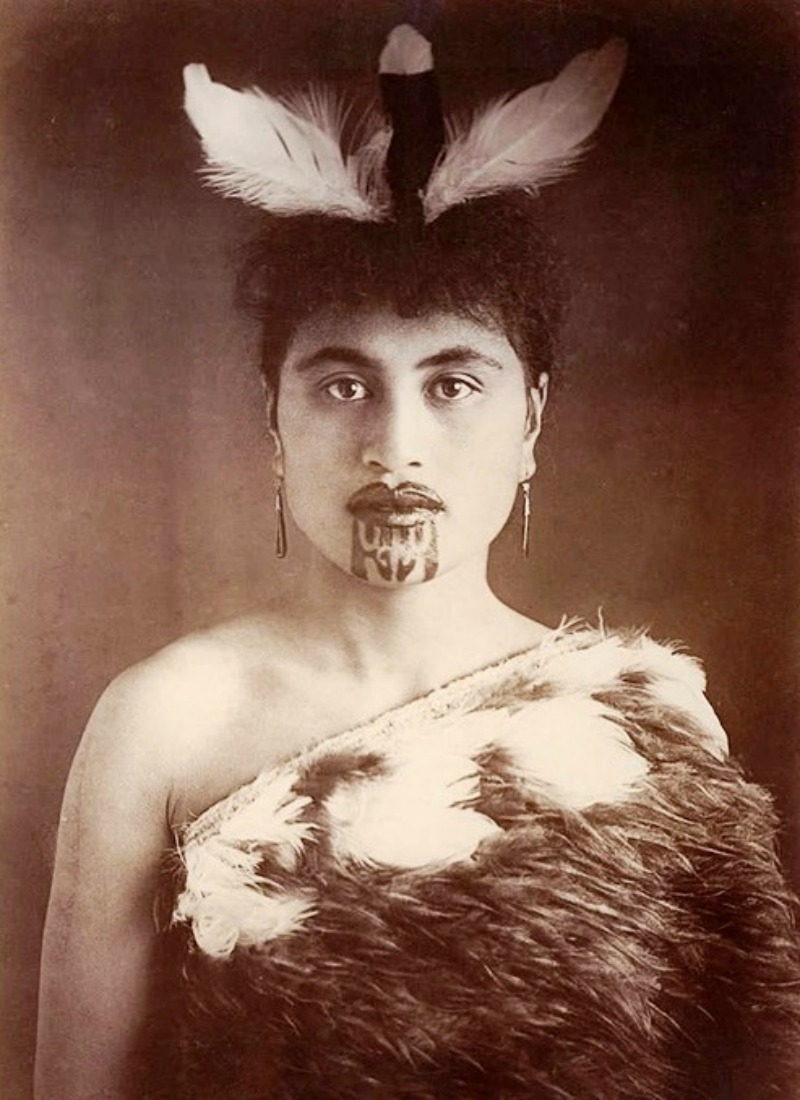

Tattoos, for the Māori, are actually sacred. These facial and body designs, which are worn by men and women, serve as their identity markers – describing their status, social position and lineage in their tribe. It is also a vehicle for storing a person’s spiritual being (tapu) after they die.

Historical Records

Gottfried Lindauer, an artist from Bohemia in the Czech Republic, came to New Zealand in 1873. He was fascinated with the Māori and their culture. He completed more than 100 portraits by the end of the 19th century. The portraits he created, exhibited in the Auckland Art Gallery are very important to the history of New Zealand not only because it precisely recorded some of the most sophisticated and artistic tattooing that were produced during that time, but also because many of those that sat for the portraits played major roles in the formative years of the country.

The Moko

There are beauty aspects to having male facial moko. During ancient times it was considered a mark of achievement and adulthood. It symbolized rite of passage.

Facial moko was usually done from the forehead down to the throat. The effect, when finished resembled a mask, which strengthened or softened the facial features, enhanced the bone structure and confirmed the wisdom of an orator or a shaman and a warrior’s virility.

It drew attention to the lips and eyes, and depending on the skill of the artist, can correct facial flaws. Each line in the moko is a testament to the courage of the person having it, because the Māori technique was an exacting and painful process.

Technique

The technique that the Māori used for the moko was different. Pacific people used comb-like tools. The Māori on the other hand used bone, shell or metalchisels that were scalpel-sharp. The chisels are dipped in ink and tapped with a mallet. They cut through the skin (and sometimes the flesh) and left scars, creating ridges and grooves on the chin, eyelids, forehead and cheeks and filled with ink.

Each facial moko is different. For a woman, the designs were restricted to central part of the forehead (not generally done today), the nostrils, darkening the upper and lower lips (solid dark blue), and a design on the chin (kauae) and down the throat.

Traditional moko used different types of inks. Burned wood, such as Kauri gum was usually use for facial ink while the ink for the body comes from the burnt fungus that grew on the heads of vegetable caterpillars.

Designs

Each design represents a symbol. The facial tattoos indicate high birth while men that were tattooed from waist to knee during ancient times have undistinguished ancestry. A warrior usually have double-headed fern fronds. Most of the moko designs consist of intricately patterned spirals and curved shapes.

A person’s ancestry was shown on each side of the face and depending on the tribe, denoted the father’s side on the left and the mother’s side on the right. If oneside of the family has no rank, that side would not be tattooed. Those with no rank do not receive a moko on the forehead.

Revival

In recent years, there has been a surge in interest in tā moko and musicians like Ben Harper and Robbie Williams and sports personalities as Mike Tyson and players of the New Zealand rugby team, the All Blacks, have received Māori tattoos.

According to many artists, Maori tattoos are among the most unique designs in the world, with their flowing design that ergonomically fit the shape of the body.

Photo Attribution:

Featured and 1st image by Stuartyeates at en.wikipedia [CC-BY-SA-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons

2nd image by Arthur James Iles (1870 – 1943) (New Zealander) (Photographer, Details of artist on Google Art Project) [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons