Much of what the masses know about the Japanese came in the form of information that traveled through the Internet: how weird they are with their Penis Festival, how peaceful they are, and how efficient they are. But apart from the mainstream exposure of the world to Japanese Art in the form of anime, manga, and video games people don’t really know much about anything when it comes to the traditional themes of Japanese art, which is strange because these themes do appear in anime, manga, and video games often, especially when the story portrayed has something to do with Japanese culture and life.

The Japanese, since they do own this culture, know these themes by heart, so when one props up in a painting, or a song, or in an anime, they’re very quick to recognize it. Such themes have deep histories behind them and those who researched them seem to find fondness and beauty in them. Manga itself, for example, is a traditional piece of Japanese art, the meaning of which has changed over the years until we now recognize them as the black-and-white comics that portray this generation’s pop culture icons, Back in the Tokugawa era, the word was used to mean a simple sketch or a casual drawing, kinda like the ones Rennaisance artists would draw in the streets of Paris.

Holidays

For example, Japanese holidays have been popular motifs in their art. Japan, just like any country, is rich with holidays. The country is influenced by Buddhism and Shinto in the past, giving their culture lots of gods and goddesses to worship and to celebrate as colorful festivals.

One example of festivals used as motifs is the Tanabata Festival, which is celebrated every July 7, though traditionally it is supposed to be on the 7th night of the 7th lunar month when the stars of Vega and Altair are seen near each other. According to the story, it is the time when Shokujo, the daughter of the Lord of Heaven, is reunited with her lover, the Heavenly Herdsman, Kengyu.

Another festival that’s a popular motif is the Setsubun Festival, where house owners would roast beans and would shout “おに は そと、ふく は うち!” (“Oni wa soto, fuku wa uchi!” which translates to, “Demons out, Good Fortune in!”). Finally, there’s the annual New Year festival, when people all over Japan flock together to shrines to greet the New Year and pray for good fortune.

People

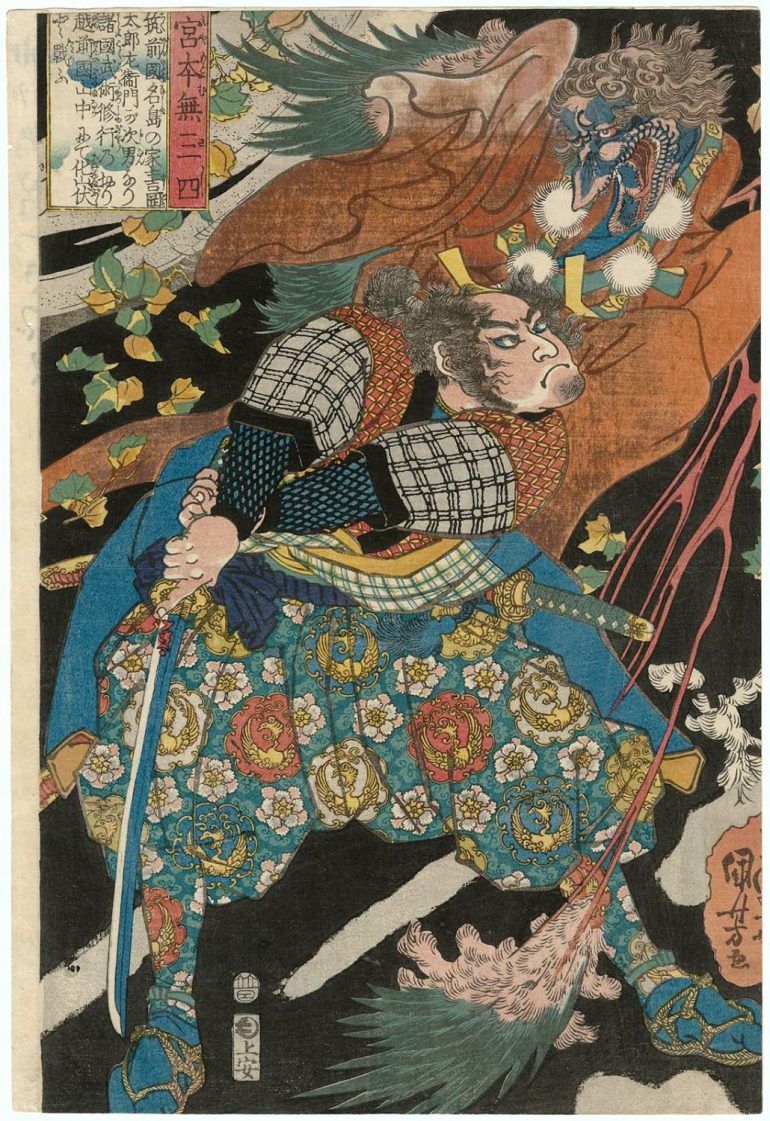

Japan’s history also has a colorful cast of characters that are used as motifs in art, and are too many to discuss in one article. The most famous of them is the celebrated samurai, Miyamoto Musashi, who is an artist himself and is known as the first samurai to develop the fighting art using two samurai swords, a difficult technique called “nitoryu“. Then there’s Tomoe Gozen, wife of Minamoto no Yoshinaka. Legend tells that she fought against three strong men at the end of a legendary campaign with her husband. Her husband was killed, but she made a name for herself and was even said to have smashed a pine tree into splinters when an enemy swung it towards her, with her bare arms.

Religion

As mentioned earlier, Japan was influenced by both Buddhism and Shinto. Shinto, meaning “a way with the gods” is Japan’s native religion. They worship every force of nature, every concept of Japanese life, and imagined the divine pantheon as having “Eight Hundred Myriad Gods” as well as having a few powerful demons here and there as the gods’ adversaries. Despite the immensity of characters portrayed in art, Shinto has a surprisingly simple teaching: “Follow the impulse of nature, and obey your Emperor.”

Buddhism came to Japan from China, and this too was morphed into a brand that’s uniquely Japanese: Zen Buddhism. The monks who followed this religion, and the deeds they are remembered for, are the usual subjects portrayed in Japanese art.

First Image: Ukiyo-e print of Miyamoto Musashi, by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, via ukiyo-e.org

Second Image: Tanabata being celebrated, by Torii Kiyonaga, via hullohollotoll.wordpress.com