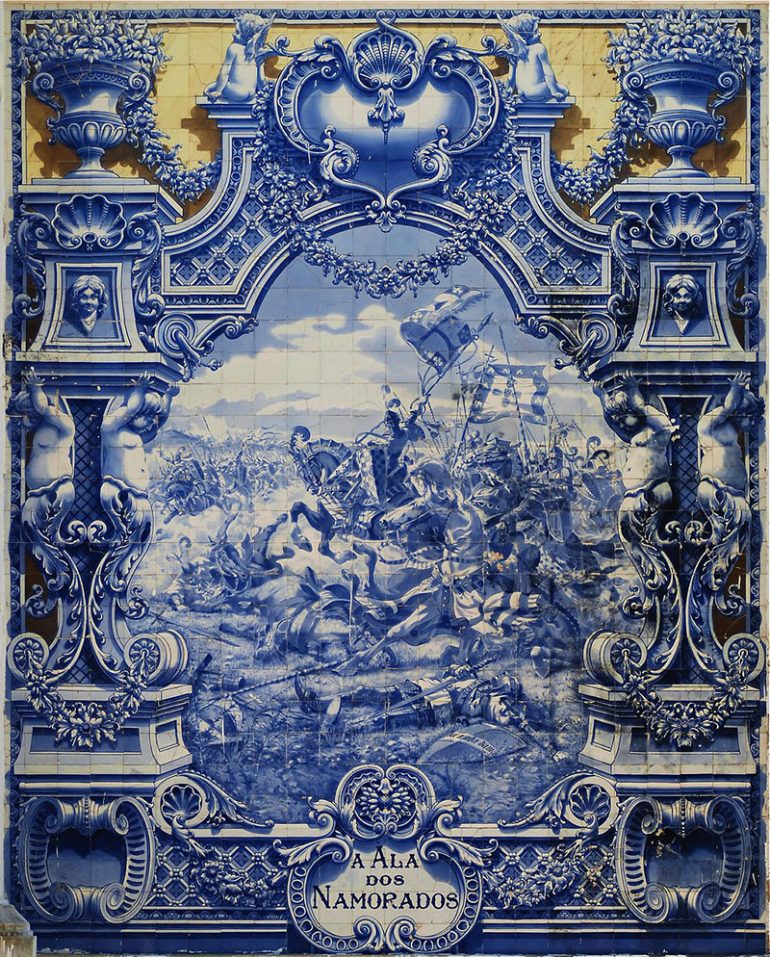

Azulejos can be found nearly everywhere in Portugal. They adorn the walls of churches and other sacred places, simple houses, shops and other public places. Their design greatly varies from symmetrical patterns; a depiction of a moment in history, to simple street signs and house numbers. Aside from being decorative, these tiles also serve as protection against heat, noise and moisture.

The use of glazed tiles originated in Egypt but it was the Portuguese who developed and refined it into an art form. From the 18th century until today, the Azulejos continue to be an important part of Portugal’s architectural design.

Origins

The term Azulejo was coined by the Moors from the Arabic word az-zulayj which means “polished stone,” an idea branching off from Roman mosaics. Early tile work showed evidence of Arab influences with floral themes or interlacing geometric designs.

Seville, one of Spain’s major cities became a center of Hispano-Moresque tile industry where the earliest form of Azulejos, the alicatados became popular. These were tiles glazed in a single color and then cut into geometric shapes, which are later assembled to form geometrical patterns.

Aves e ramagens (birds and branches) is another form of Azulejo composition that became popular between 1650 and 1680. Printed textiles that were imported from India depicting Hindu symbols, such as birds, flowers and other animals became the inspiration for the designs in these tiles.

From using several colors such as white, green, yellow and blue, the tiles became predominantly blue and white, which were very fashionable during the 17th century. The shift was influenced by another highly prized import, the blue and white porcelain from the Ming Dynasty.

Precious import

Jan van Oort and Willem van der Kloet produced large tile pieces portraying historical scenes in their workshop in Amsterdam during the 17th century, supplying for their wealthy Portuguese customers like the Palace of the Marqueses da Fronteira, located in Benfica. Between 1687 and 1698 however, King Pedro II halted all imports of Azulejos and Gabriel del Barco’s workshop took over the production of the tiles. Before long, academically trained Portuguese artists designed and produced large, home-made blue-and-white figurative tiles. These eventually became the prevalent style, replacing the old style of repeated and abstract patterns.

The “Golden Age of the Azulejo” came between the late 17th and early 18th centuries, also known as “Ciclo dos Mesteres” or the Cycle of the Masters. A stir of large orders from the Portuguese colony in Brazil resulted in mass import production, favoring repetitive tile patterns, which were cheaper and faster to produce over large one-off designs. Together with extravagant Baroque design elements, Azulejos adorned the walls of churches, monasteries, palaces and ordinary houses.

Emergence of tile designers

The early 18th century has seen the prominence of several master designers like António Pereira, the father-and-son team of António and Policarpio de Oliveira and Manuel dos Santos. Master PMP, who was only known by his symbol and his partners Valentim de Almeida and Teotónio dos Santos, as well as Bartolomeu Antunes and his student, Nicolau de Freitas also became quite popular. They called the style of this period the Joanine style, as their production concurred with the reign of King João V (1706–1750).

Cut-out panels of Azulejos featuring life-size depictions of footmen, halberdiers, noblemen or ladies dressed elegantly, usually affixed in entrances of palaces, like the one in Palácio da Mitra are called Figura de Convite or “Invitation Figures.” Invented by Master PMP, their purpose is to welcome visitors into the palace. These masterfully created tiles can only be found in Portugal.

The Art Deco-Azulejos style emerged during the 1930s, led by its principal artist António Costa. The entrance hall of the São Bento railway station in Porto is decorated with a staggering 20,000 Azulejos depicting historical scenes in a romantic, picture-postcard theme created by artist Jorge Colaço.

The large abstract panels that decorated the initial nineteen stations of the Lisbon Underground are attributed to Maria Keil, which was placed between 1957 and 1972. Through her work, she ushered in the revival and the updating of the art of the Azulejo. By 1988, more contemporary artists were charged to decorate the newer train stations.

The traditions of producing Azulejos are still alive in most of the countries that went under Spanish or Portuguese rule like South America, Africa (Mozambique and Angola), Goa and the Philippines. The largest collections of Portuguese tiles in the world are found in the Museu Nacional do Azulejo in Lisbon.

Photo Attribution:

Featured and 1st image by I, Alvesgaspar [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC BY 2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons

2nd image by By Etan J. Tal (Own work) [CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons